Click here to download the PDF file.

FROM IDLIB TO THE ALEPPO COUNTRYSIDE

“We liberated the rural parts of [Aleppo] province. We waited and waited for Aleppo [city] to rise, and it didn’t. We couldn’t rely on them to do it for themselves so we had to bring the revolution to them.”[1] This comment by a Free Syrian Army (FSA) commander with the nom-de-guerre of Abu Hashish highlights the urban-rural division in Aleppo. For decades the city, dominated by its upper middle class and bourgeois residents, became increasingly detached from its surroundings.[2] The remark also describes the dynamics of the conflict which stretched north from the Idlib countryside, reached northern Aleppo province and then arrived in the city.

It also indirectly reflects the government’s military strategy throughout Syria. By the time the conflict arrived in the Aleppo region, it was clear that the regime was focused only on keeping control of urban centers and key military positions. They lacked the capacity to hold more territory.[3] The rebels tried to hold their ground in major cities such as Homs and Idlib. By early summer 2012, the government had pushed them to the countryside through massive bombardments. This city vs. countryside mentality also reflects the fact that the government enjoys more support in urban centers.

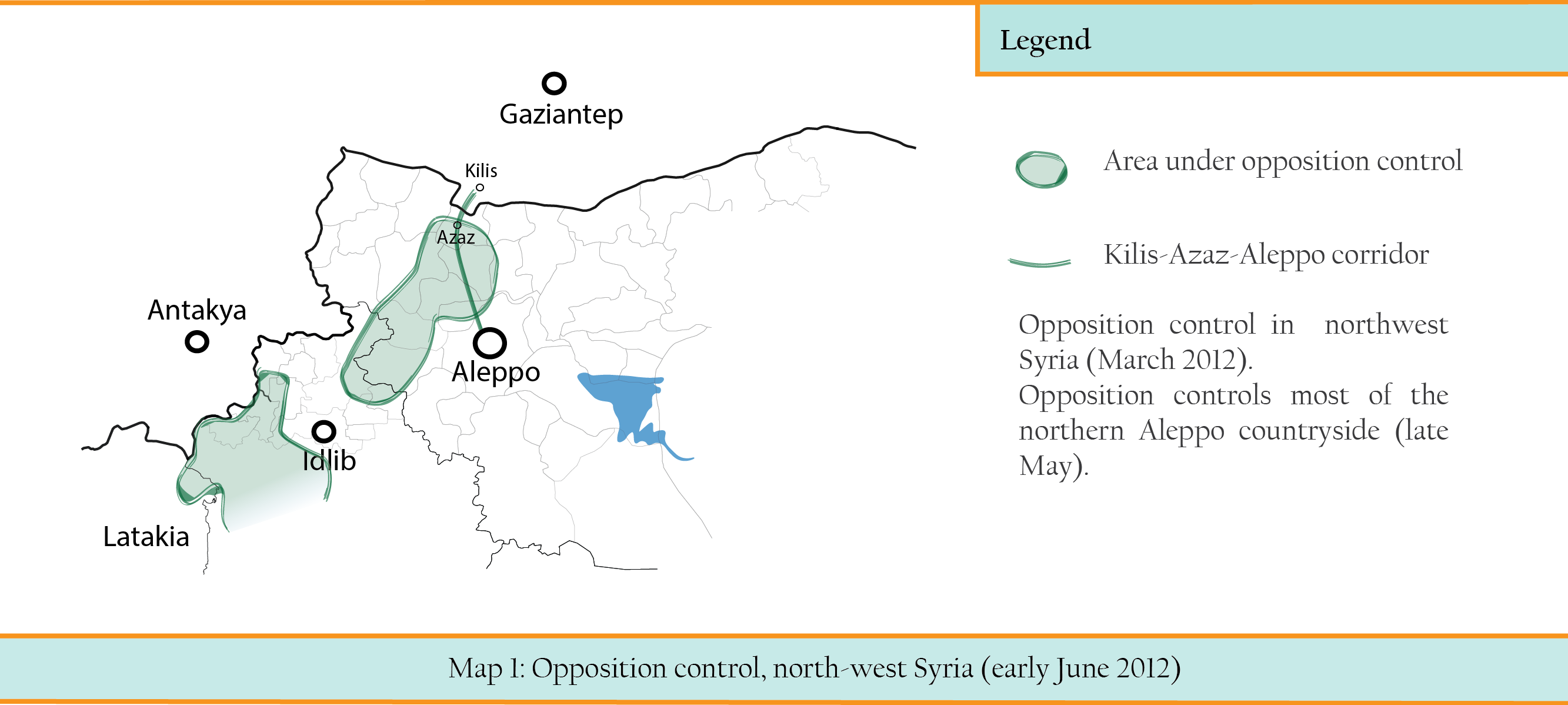

When the conflict reached north of Aleppo, a similar scenario was underway. Locals in many villages, joined by defectors, formed small armed groups in towns like Azaz, Tal Rafat and Mare’. This led to the emergence of a decentralized network of armed groups fighting the regime presence in their villages and towns. The first major clashes took place in February and March 2012. By early July, northwest Aleppo province, including the Azaz-Aleppo highway, was mostly out of government control. By taking weapons from government facilities and receiving arms from supporters through Turkey they began preparing for an offensive on the city.

Source: Institute for the Study of War

Source: Institute for the Study of War

In 2012, the FSA organized the main rebel armed groups throughout the province under the umbrella of the Aleppo Military Council (AMC). Most of these groups operated on the Kilis-Azaz-Aleppo axis, but there were also fighters in al-Bab city and in the western countryside.[4] Even though the council strengthened ties among the rebel groups, it failed to create a clear command and control strategy. Sometimes coordination in northern Aleppo province did not extend beyond the neighborhood level.[5] In mid-July, before fighting reached the city, more than two dozen rebel groups came together to form the Liwa al-Tawhid (the Tawhid Brigade[6]). It became the largest group within the council and the strongest in northern Aleppo Governorate.

Before July 2012, aside from some protests at Aleppo University[7] and one large attack, the city was mostly calm. On 10 February 2012, two suicide bombs hit the Military Security Intelligence office and the Public Order Enforcement Barracks. The attacks killed 28 and wounded 235, according to the government.[8] Jabhet an-Nusra (JN) later claimed responsibility.

Among regime supporters, there was a sense of invincibility. Many said the army would clear Aleppo in two days if there was a rebel attack.[9] Elites, who mostly lived in what would become government-controlled western Aleppo, once again ignored tensions that had built up in poorer districts in eastern parts of the city. When fighting began, rebels rapidly won control of the east of the city, dividing Aleppo.

BOX 1: Aleppo Military Council and Liwa al-Tawhid

The Aleppo Military Council (AMC) comprised two major coalitions: the Fateh and Liwa al-Tawhid. Liwa al-Tawhid, the larger and more influential, have three major subunits: the Daret Ezza, Fursan al-Jabal and Alwiyet ash-Shamal brigades, each operating in different areas of Aleppo province. Ahrar ash-Shamal, was the core fighting force of the Tawhid Brigade.[10]

The Liwa al-Tawhid military coalition coalesced in mid-July 2012 as the largest fighting force in Aleppo province. Although one of its leaders claimed it had 3,500 fighters,[11] this number is likely an exaggeration. The coalition led the battle for the city.

Although rebels have often claimed clear and organized coordination mechanisms, this has rarely been the case on the ground. Many ideological and religious differences exist among these forces. One of Tawhid’s battalions, Sheikh Ibn al-Taymiyya, had clear Salafi ideas, which contradicted the official position of the AMC. The council was also unable to control the behavior of all groups under its nominal control. While AMC leaders claimed they followed international humanitarian law, the Tawhid brigade summarily executed 10 shabbiha (paramilitary forces loyal to the regime) from the Sunni Berri clan.[12] The family was known for its smuggling and other illicit businesses in the city and were closely allied to the Assad regime. The clan helped suppress protests in Aleppo early in the conflict and later took up arms against the Tawhid Brigade in July 2012.

The Tawhid-affiliated group Nur ad-Din al-Zanki was the first to enter the district of Salah ad-Din district in July. Gradually, Tawhid became the most influencial group in the city. It had a pragmatic policy of cooperating with many groups and accepting money from many donors. It openly cooperated with Jabhet an-Nusra (JN) and built links to the Muslim Brotherhood, which was supported by Turkey, as well as with Salafi funders in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait.[13]

By October 2013, Liwa al-Tawhid had between 8,000 and 10,000 fighters and 10,000 other members.[14] It created two foundations: Tawhid Medical and Tawhid Media. It also took part in establishing the Sharia Council in Aleppo.

Weeks before violence struck Aleppo in July, talks began in Geneva to stop the spreading fire in Syria. The core of the so-called Geneva I meeting was the six-point plan from Kofi Annan, the UN and Arab League Special Envoy. The two key elements of his plan were to agree on a ceasefire and to start a political transition in Syria. The Security Council supported this plan by adopting Resolutions 2042[15] and 2043[16]. The plan was also officially accepted by Damascus on 27 March 2012.[17]

The first step of implementing the Annan plan was to stop the fighting. The government was supposed to remove military equipment from civilian areas. Based on the UN resolutions, 300 unarmed military observers were deployed to monitor the situation. Despite these efforts, the ceasefire was shaky and failed in mid-April.[18]

In spite of this failure, Annan’s initiative helped Russia, the United States and the opposing Syrian sides agree on key principles to resolve the conflict – the Geneva Communiqué.[19]

The communiqué set up an overall transition road map. It proposed an inclusive transitional government with strong executive powers; called for a national dialogue; a new legal order and free and fair elections. Given Russian and U.S. polarization and escalating violence on the ground, this was an important achievement. One major question remained: would Assad stay or go? The United States said he must go.[20] Russia insisted this issue should be left for the Syrian people to decide.[21]

BRINGING THE CONFLICT TO THE CITY (JULY-AUGUST)

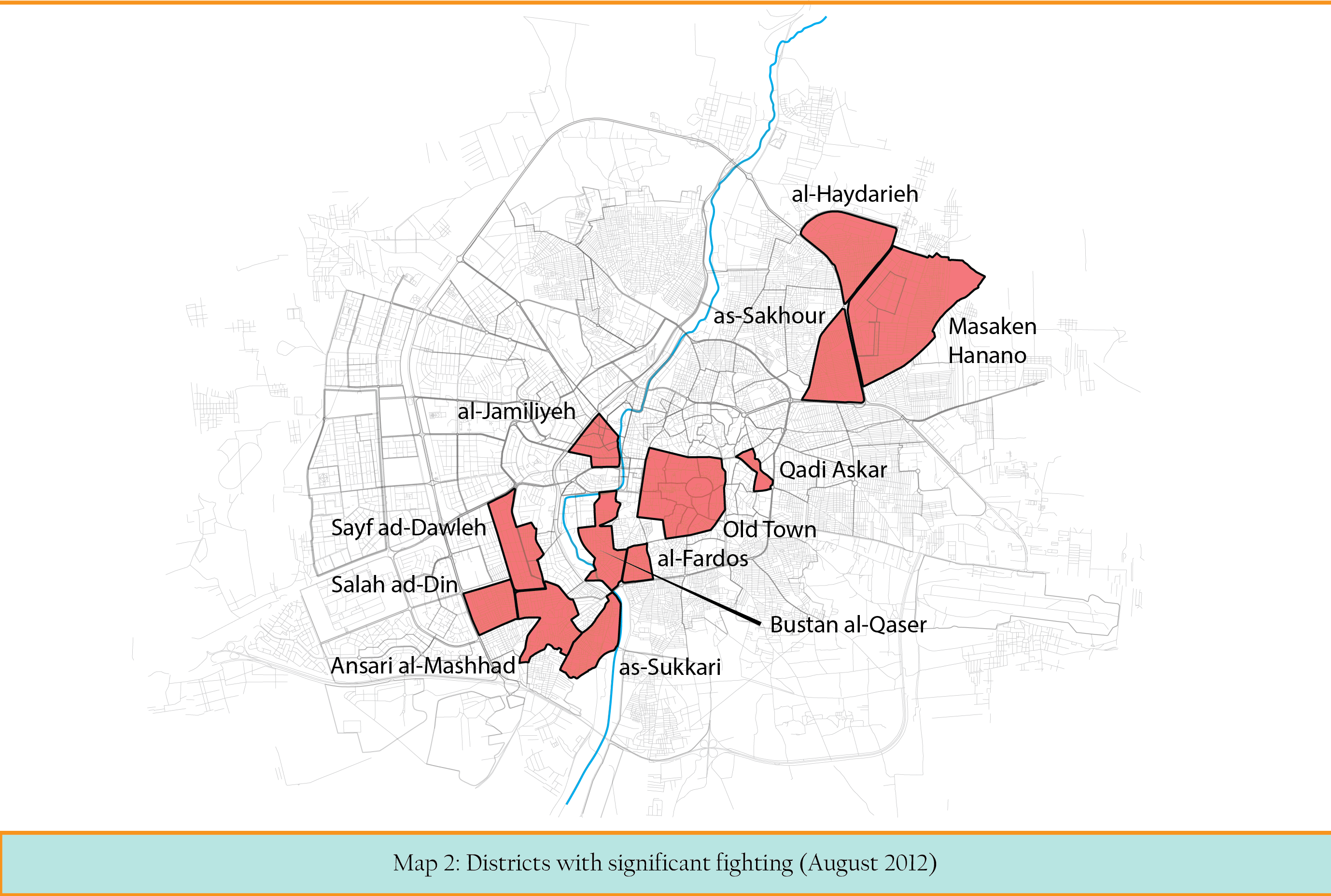

The first major clash in Aleppo took place in the southwestern district of Salah ad-Din on 19 July 2012. Rebels passed through government checkpoints surrounding Aleppo and established an armed presence within the city. By the end of July, the rebels had taken over Salah ad-Din, which was to become their stronghold and the main target of government shelling. There were hit-and-run clashes mainly in eastern areas where rebels attacked security facilities and checkpoints. Liwa al-Tawhid played a leading role in this campaign.

The government was poorly prepared. To stop the rebels from taking ground in the city, it fortified security and government buildings, threw up checkpoints and blockaded many streets. It started striking rebel areas using tanks, artillery and helicopters but did not engage in a major ground offensive until 7 August. There was no clear frontline, but the rebels soon dominated the eastern areas.

For two weeks, the government prepared an offensive on the southwest. On the rebel side, former Syrian Army Colonel Abduljabbar al-Oqaidi, one of the leaders of the opposition Aleppo Military Council, said they were reinforcing their positions and preparing for a major battle.[22] This battle started on 7 August when government forces launched a ground offensive, with air support, to retake Salah ad-Din. Despite showing strong resistance, the rebels were pushed to the adjacent neighborhoods of Seif ad-Dawleh and al-Mashhad due to ammunition shortages and a lack of heavy weapons.[23] Government forces then prepared for an attack on as-Sukkari district, a second rebel stronghold.[24]

The violence led to the first major exodus from the city, with 300,000 people fleeing in July and August to Turkey or other parts of Syria.[25] In the first two weeks of October alone, Turkey registered 8,600 refugees.[26] The monthly death toll in the province increased from fewer than 200 people to more than 300 in July and it again exceeded 300 in August.[27]

The humanitarian situation in the city deteriorated rapidly. Amnesty International reported that neither side was respecting International Humanitarian Law which: 1) draws a distinction between civilians and military forces; 2) forbids indiscriminate shelling 3) bans mistreating prisoners and former fighters. The report accused the government of the worst offenses as it was shelling civilian areas.[28]

Sources: The Telegraph, BBC News, Aljazeera English

Sources: The Telegraph, BBC News, Aljazeera English

BOX 2: The Joint Command for Revolution’s Military Council (September 2012)

The joint command aimed at improving coordination among Free Syrian Army (FSA) affiliates across the country operating under provincial military councils. The new structure had a General Command led by five prominent general brigadiers and 14 provincial military councils. Aleppo Military Council (AMC), with Liwa al-Tawhid playing the major role, came under the Joint Command. Officially, the command embraced secularism, but on the ground member groups had different ideological backgrounds and coordinated with others, including Jabhet an-Nusra (JN). It was short-lived mainly due to Qatari and Saudi competition to control the politics of the Joint Command.[29]

Syrian Liberation Front (Previously Islamic Front to Liberate Syria) (September 2012)

The front was the largest coalition in Syria. It included up to 15 different groups most prominently, Suqour ash-Sham (active in Idlib), Kataeb al-Farouq (active in Homs) and Liwa al-Tawhid (Aleppo). The coalition included groups with Salafi views as well as some moderates. Although this umbrella organization was separate from the FSA, on the ground, most of the groups cooperated. To make the map of armed actors even more confusing, some were officially part of both the Joint Command and the Liberation Front.

Syrian Islamic Front (December 2012)

The Syrian Islamic Front, which was dissolved in November 2013, was the largest national Salafi group. It included 11 groups, most prominently, Ahrar ash-Sham, Haraket al-Fajer al-Islamiyeh (both strong in Aleppo) and Liwa al-Haqq, all of which supported a state under Islamic law. Although its proclaimed political vision of the alliance was different, it sometimes cooperated and coordinated with Jabhet an-Nusra (JN) and/or the FSA against government forces. At the same time, occasional disagreements and even clashes broke out between the Syrian Islamic Front and these two groups.

– On the ground, these coalitions and alliances lived a different reality. Despite ideological differences, oftentimes groups from different coalitions closely cooperated with each other.

– Many groups joined multiple commands and coalitions at various times: the Liwa al-Tawhid in Aleppo was in both the FSA-affiliated Aleppo Military Council and the Syrian Liberation Front.

– These coalitions and alliances should not be seen as coherent and well-structured organizations; allegiances shifted constantly.

– Many individual groups, regardless of coalition, maintained their own sources of funding. This made clear command and control very difficult.

– Many donors, especially Qatar and Saudi Arabia, were competing for a stronger voice in the structure of rebel coalitions, especially those affiliated with the FSA. This contributed significantly to the fragmentation of the opposition.

– There was a noticeable increase in the influence of radical ideologies, particularly Salafism.

THE OLD CITY ON THE FRONTLINE (SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER)

On 27 September, the opposition launched an offensive and slightly redrew the frontlines in the districts of al-Midan, Suleyman al-Halabi, al-Hamidiyeh and the Old City. In this way, areas under opposition control included the Souq al-Mdeeneh, Bab Antakya, Bab Jnen, Bab al-Hadeed, Bab an-Nasr (the latter four are the western and northern gates of Old Aleppo), the Aleppo Citadel and the adjacent areas. This frontline has changed little during the course of the conflict because neither side has committed sufficient ground forces to enlarge its territory. Rather, they have concentrated on fortifying their defenses. Increasingly, Aleppo has become a divided city with each side developing its own administration and way of life.

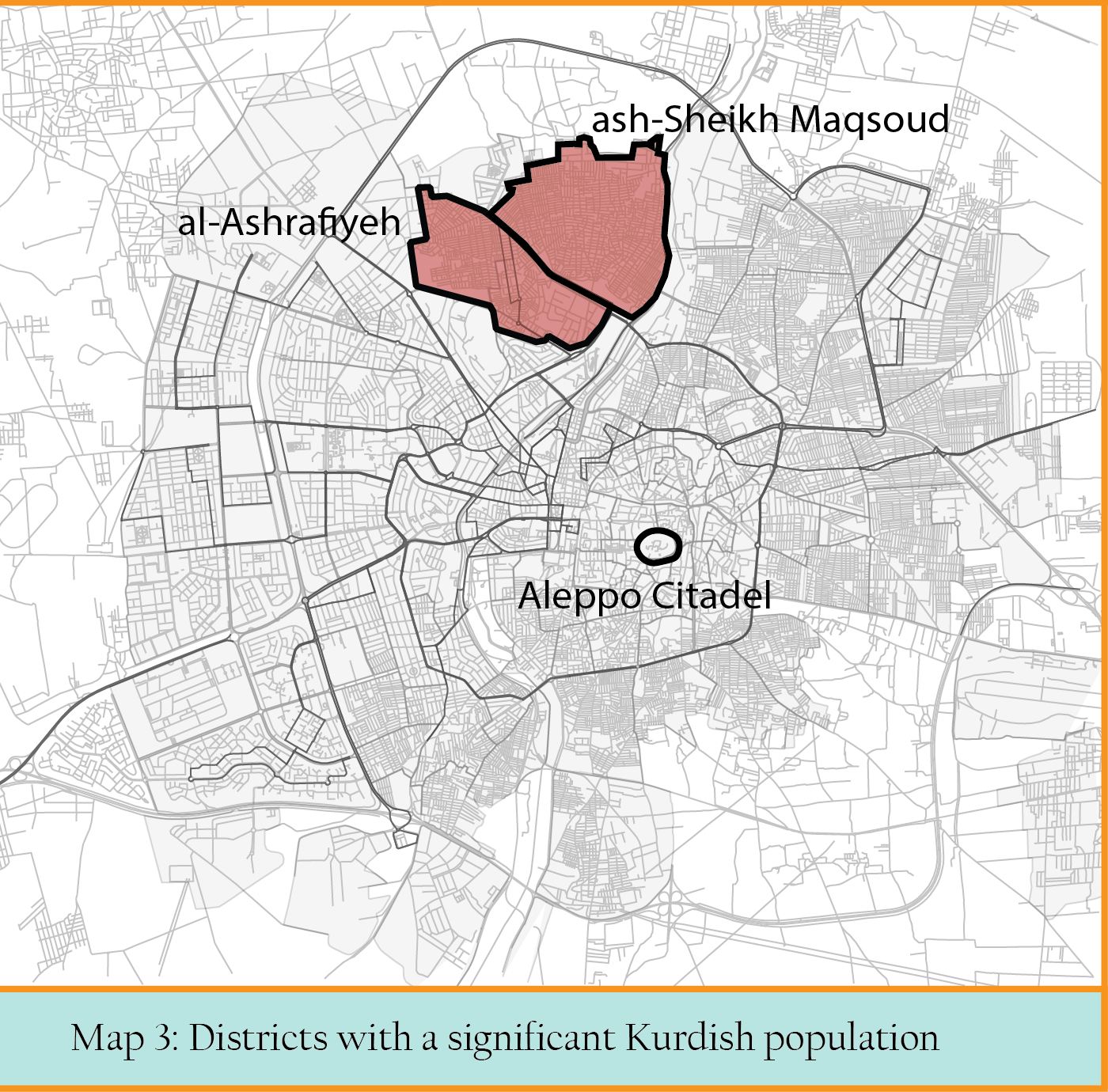

Besides the government and the rebels, a third force became involved in Aleppo: the People’s Protection Units/Women’s Protection Unit (YPG/YPJ), a mostly Kurdish militia based in two neighborhoods in the north of Aleppo city, al-Ashrafiyeh and ash-Sheikh Maqsoud.[30] The YPG/YPJ claimed to maintain a neutral position by defending its territories against both the opposition and the government. Tension between the rebels and the Kurdish forces emerged rapidly not just in Aleppo but also in other areas. Rebels accused the YPG/YPJ of cooperating with the government in the ash-Sheikh Maqsoud and al-Ashrafiyeh districts.[31] At the end of October, opposition forces entered al-Ashrafiyeh district and clashed with the YPG/YPJ, causing significant casualties and kidnapping many Kurdish fighters and civilians. A Kurdish official said that the rebels, by entering al-Ashrafiyeh, had violated a gentlemen’s agreement. The confrontation ended with a truce on 5 November.[32]

On 2 October, Syrian opposition figures established the Syrian National Council (SNC) in Istanbul. The majority of its members were exiled Syrians. The SNC earned international legitimacy when 70 countries recognized it as the representative of the Syrian people during the Friends of Syria Summit in Istanbul on 1 April 2012. Headed by Burhan Ghalioun, a Syrian academic residing in France, it became the main Syrian political opposition at the international level.

In October, Lakhdar Brahimi, the Algerian diplomat who had taken over from Annan as special envoy for Syria, suggested another truce in Aleppo. Under the plan, combatants would begin a ceasefire on 26 October, the first day of the Muslim holiday of Eid al-Adha.[33] The early hours of the truce were promising but sides soon restarted the war and accused each other of violating the ceasefire.

On 29-30 September, the Souq al-Mdeeneh was extensively damaged by fire possibly due to an exchange of shelling between the rebels and government forces. Some suggested it was the result of deliberate arson by the rebels. The fire destroyed between 700 and 1,000 shops.[34] On 1 October, UNESCO Director-General Irina Bokova said that in addition to the human suffering, the “fighting is now destroying cultural heritage that bears witness to the country’s millenary history.”[35]

On 10 October, the Liwa al-Tawhid attacked the Grand Umayyad Mosque to expel government forces stationed there. Within a week, the mosque had been badly damaged by fire and much of it had been destroyed.[36]

In Aleppo, residents struggled with inflation, shortages and an exploitative black market.[37] On 8 September, fighting destroyed one of the city’s main drinking water pipes in Bustan al-Basha.[38] Opposition activists blamed regime aerial bombing for the damage, which they said targeted the east. Water shortages soon affected the whole city.[39]

BOX 3: Syrian Political Opposition

When conflict broke out, political opposition groups proliferated. As of the winter of 2012, two prominent opposition groups had emerged: The Syrian National Council and the National Coordination Committee for Democratic Change.

Syrian National Council (SNC)

The SNC became the main representative of the opposition at the international level after 70 countries recognized it during the Friends of Syria Summit in Istanbul on 1 April 2012. Burhan Ghalioun, a secular Syrian academic residing in France, became its first chairman. Abdulbaset Sieda, a Kurdish writer and activist followed him in June 2012. Since November 2012, the organization has been headed by Christian opposition activist George Sabra.

According to its charter, the council represents the Local Coordination Committees, a grassroots, countrywide network of activists who organized the protests. The Muslim Brotherhood, those involved with the Damascus Declaration (a group of dissidents who left the country between 2001 and 2005), as well as Kurdish and Assyrian representatives joined the group.[40] The Muslim Brotherhood, being the best organized and numerous, dominated the Council.[41]

Soon, internal divisions became critical. By November 2012, it was clear that the Council could not lead the resistance.[42] It was not only aloof from day-to-day activities inside Syria, it also had a troubled relationship with the Free Syrian Army. In November 2012, the National Coalition of Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces (National Coalition) was established in Doha. The Council was absorbed into the new Coalition. The National Coalition replaced the SNC as the main internationally-recognized political opposition umbrella organization.

The National Coordination Committee for Democratic Change (NCC)

Established in June 2011, it represents the bulk of Syria-based opposition groups. Unlike the SNC, its headquarters is in Damascus. Its members and their activities are largely tolerated by the Assad government, which did not recognize any opposition outside Syria. The NCC charter includes three pillars: no foreign intervention, no sectarianism and no violence or militarization. The chairman is Hassan Abdul Azim. His deputy and spokesman abroad is Haytham Manna.

Despite the fact that both political bodies supported regime change, they disagree on how best to achieve it. While the NCC favors negotiations with the government, the SNC rejects any form of dialogue. The former does not explicitly demand the removal of Assad whereas the SNC has made it clear from the early days of the conflict that he cannot play a role in the future of Syria. Finally, the NCC rejects any form of militarization, whereas the SNC has an ambiguous position. Although it considers the FSA as integral part of the revolution and agreed to provide salaries for its fighters, it does not actively support the arming and militarization of the revolution.[43]

LIMITING THE REGIME TO ALEPPO CITY

(NOVEMBER-DECEMBER)

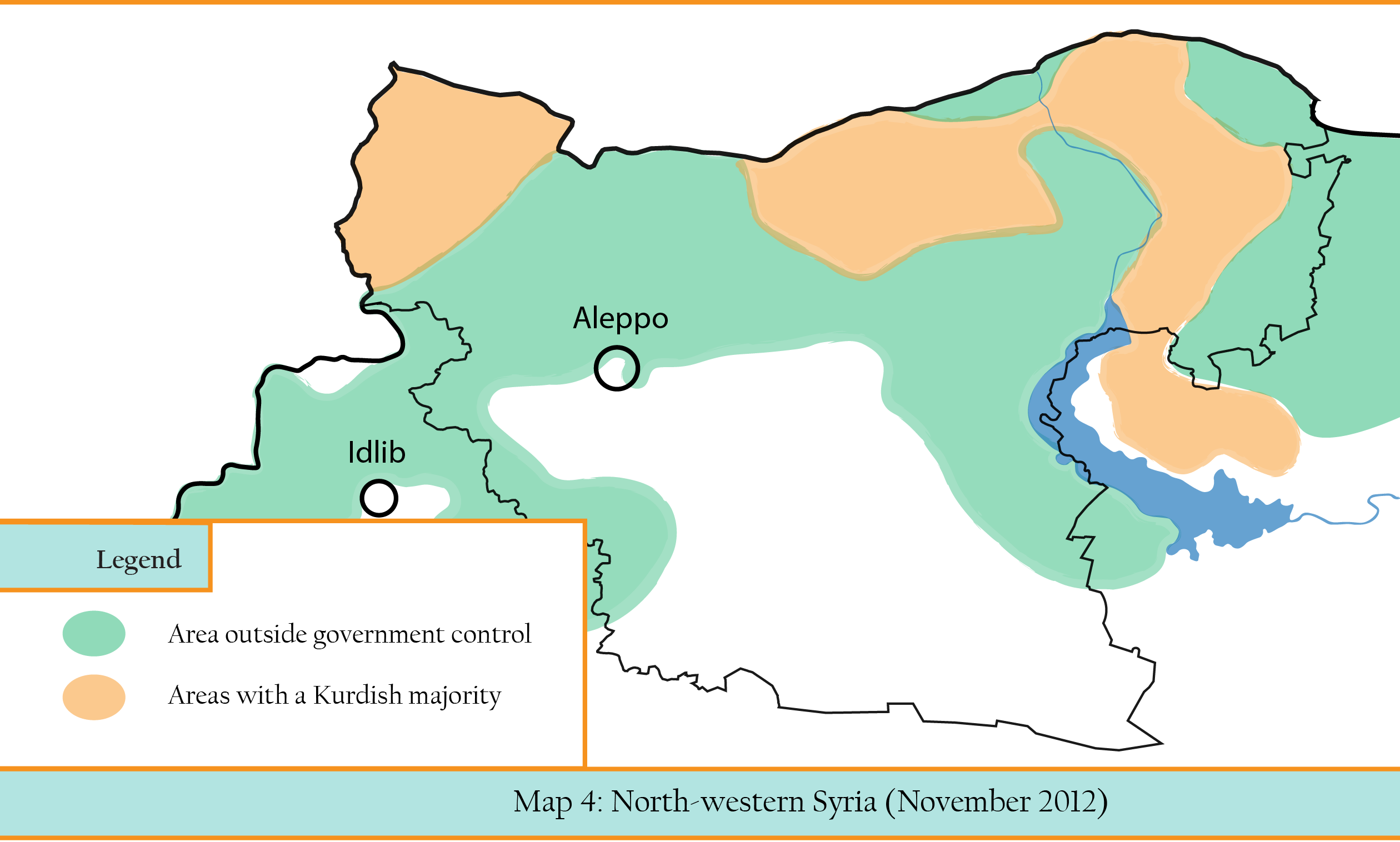

Towards the end of 2012, government forces held just a handful of positions in the Aleppo countryside. As Map 4 shows, the rebels now dominated the northwest of Syria. In early December, JN occupied the SYSACOO chemical factory, east of Aleppo, prompting Damascus to warn the UN that rebels might now be able to develop chemical weapons.[44]

Source: Institute for the Study of War

Source: Institute for the Study of War

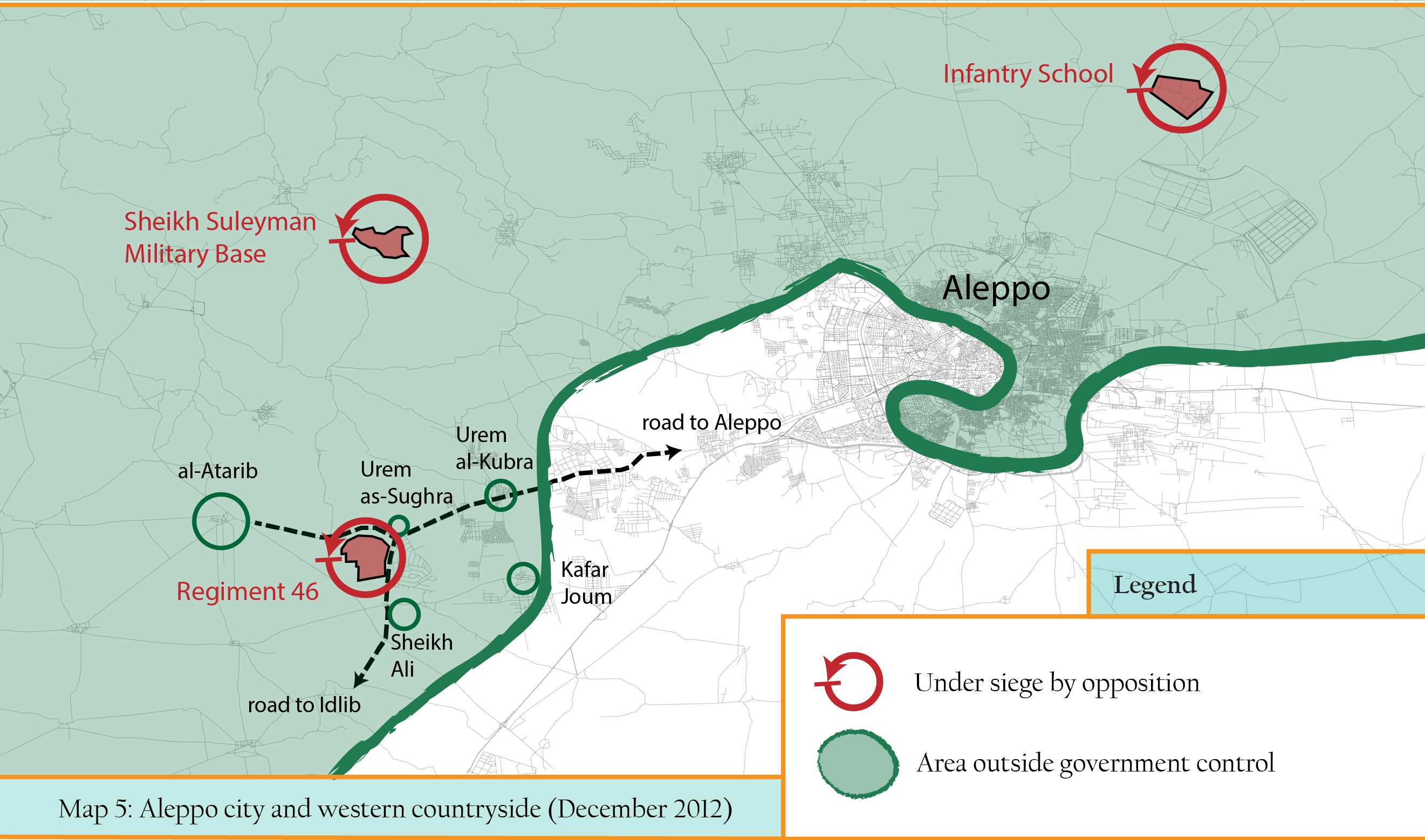

On the western front, there were two major developments. On 18 November, several opposition groups took over the Regiment 46 Base, located in western Aleppo province on the Atareb-Idlib-Aleppo road intersection from about 350 government soldiers. The rebels, who took al-Atareb to use it as a headquarters, had isolated the base by occupying four villages around it: Urem as-Sughra, Urem al-Kubra, Tal Joum and Sheikh Ali.[45] (See Map 5) Rebels claimed to have deployed about 1,500 men for this operation.[46] The al-Mutasem Billah Brigades fighting under the flag of the FSA under the command of defected General Ahmed al-Fejj, led the operation.[47]

Less than a month later, the government lost another important base in the west of Aleppo countryside known as Sheikh Suleyman. After two months of laying siege, the rebels tried to take it in late November but failed. The head of the Kataeb Nour ad-Din al-Zanki, one of the stronger groups in Aleppo, said there were about 300-400 soldiers defending the base but their morale was low.[48] Victory for the opposition came only after JN affiliates joined the battle on 10 December.[49] JN was not only better-organized and equipped, its ranks also included many experienced fighters. (See Map 5)

On 15 December, the government also lost the Infantry School just north of Aleppo city after 20 days of fighting. Liwa al-Tawhid led the operation.[50] The government was increasingly isolated west of the city. (See Map 5)

In November, a new political body was launched in Doha: the National Coalition of Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces (National Coalition). The coalition, in cooperation with Turkey, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United States and France, sponsored the creation of the Supreme Military Council (SMC) in December 2012 in Antalya. The SMC succeeded the Joint Command and enhanced coordination among rebel groups across the country. The rebels were divided into five operational fronts: North (Aleppo and Idlib), Central, Homs, Eastern and Southern.[51]

The public face was secular, but the SMC included groups such as Liwa al-Tawhid, which was both increasingly effective on the ground and included radical affiliates.[52] Even though overall command and control remained weak, the SMC did enhance cooperation among groups that were fighting on the same front. Its structure successfully included political figures such as Salim Idriss, the head of SMC, and respected field commanders. The SMC was particularly influential in the Aleppo region due to its proximity to Turkey, which made supplying weapons easier.[53]

In December, all flights were suspended from Aleppo International Airport when JN declared a “no-fly zone” and threatened to shoot down civilian planes, which they claimed the government was using to transport supplies.[54]

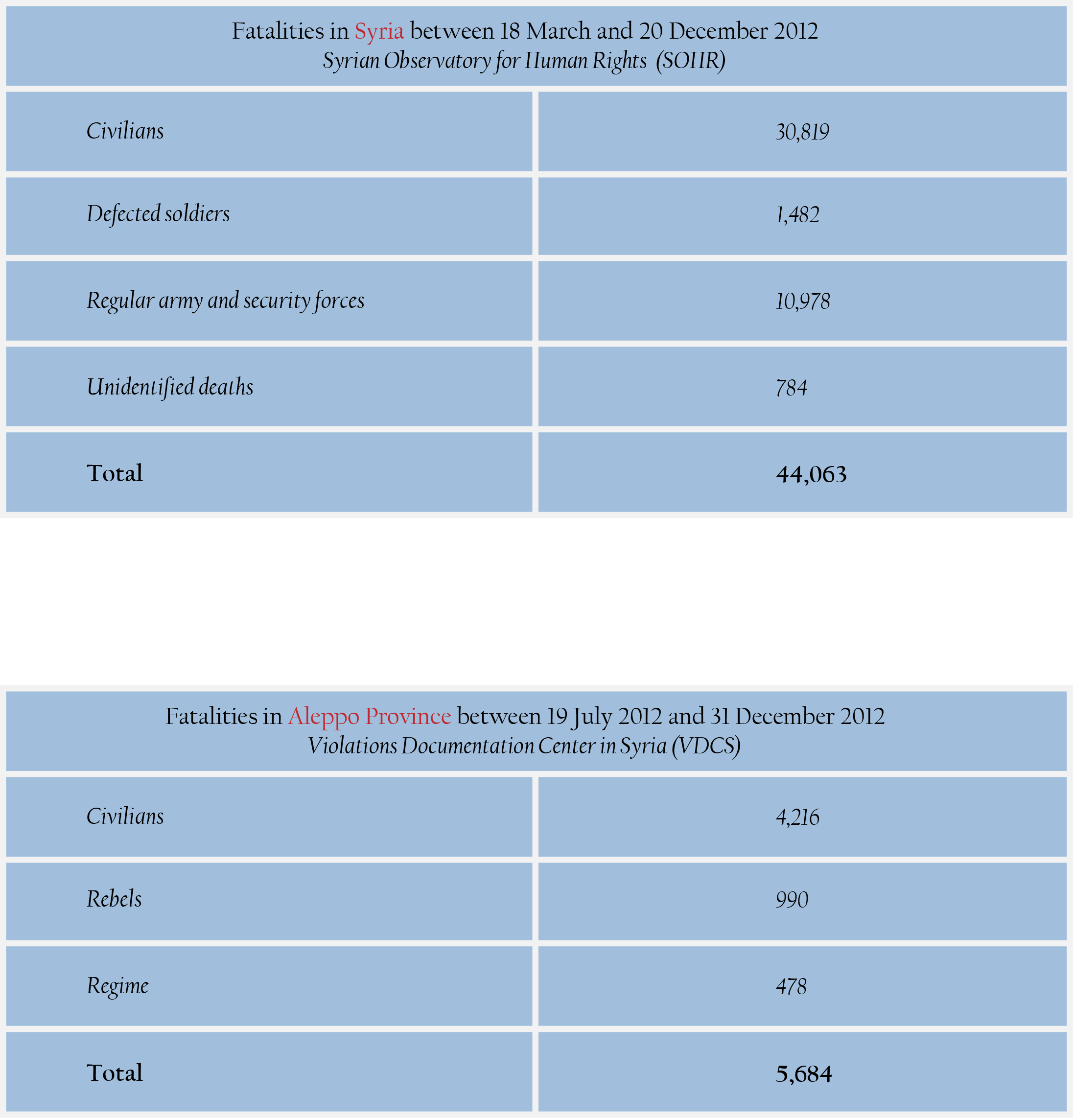

Death Toll in 2012

[1]Solomon, Erika. “Rural fighters pour into Syria’s Aleppo to fight.” Reuters. 29 July 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/07/29/us-syria-crisis-aleppo-idUSBRE86S06T20120729

[2]Imam, Ghassan. “Social struggle: the other face of Syria’s sorrow.” 7 February 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://archive.aawsat.com/leader.asp?section=3&issueno=12124&article=662454#.VWxknc-qpHw

[3]Holliday, Joseph. “Syria’s Maturing Insurgency.” Institute for the Study of War. June 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/Syrias_MaturingInsurgency_21June2012.pdf p.11; Sherlock, Ruth. “Syria’s rebels abandon territory in major cities in favour of new guerilla war.” The Guardian. 2 April 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/syria/9181867/Syrias-rebels-abandon-territory-in-major-cities-in-favour-of-new-guerilla-war.html; The Associated Press. “Inside the Syrian Resistance.” Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.ap.org/Images/Syria_%20final_tcm28-12511.pdf

[4]Bolling, Jeffry. “Rebel Groups in Northern Aleppo Province.” Institute for the Study of War. 29 August 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/Backgrounder_RebelGroupsNorthernAleppo.pdf

[5]The Associated Press. “Inside the Syrian Resistance.” Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.ap.org/Images/Syria_%20final_tcm28-12511.pdf p.2.

[6]The word “brigade” throughout this report does not refer to any standard military formation. Armed groups attach these titles to their groups although the size and importance varies widely.

[7]Ammana. “Protest erupts in Syria Aleppo University-activists.” Reuters. 13 April 2011. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/04/13/syrai-protests-aleppo-idUSLDE73C1J020110413 ; Accessed 25 April 2016. See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qadz_054nZ4

[8]DP News. “Dozens of martyrs after bombing in Aleppo. Conflicting statements about FSA involvement.” 10 February 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.dp-news.com/pages/detail.aspx?articleid=111276; BBC Arabic. “FSA claims responsibility for the attacks and not the bombings.” 10 February 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.bbc.com/arabic/middleeast/2012/02/120210_syria_aleppo_explosions.shtml

[9]Author’s experience in Aleppo in 2012.

[10]Bolling, Jeffry. “Rebel Groups in Northern Aleppo Province.” Institute for the Study of War. 29 August 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/Backgrounder_RebelGroupsNorthernAleppo.pdf p.5.

[11]Bolling, Jeffry. “Rebel Groups in Northern Aleppo Province.” Institute for the Study of War. 29 August 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/Backgrounder_RebelGroupsNorthernAleppo.pdf p.5.

[12]France24. “Video: Aleppo rebels execute members of pro-Assad clan.” 2 August 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://observers.france24.com/en/20120802-video-aleppo-rebels-summarily-execute-members-pro-assad-clan-zeinou-berri-execution-free-syrian-army-condemned

[13]Anjarini, Suheib. “Liwa al-Tawhid: the full story.” Al-Saffir. 22 October 2013. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://assafir.com/Article/324374#.UmXYOZNOIiQ

[14]BBC. “Guide to the Syrian Rebels.” 13 December 2013. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-24403003

[15]UNGA Resolution 2042. 14 April 2012. Accessed 9 May 2016 http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/2042(2012)&referer=http://www.un.org/en/sc/documents/resolutions/2012.shtml&Lang=E

[16] UNGA Resolution 2043. 14 April 2012. Accessed 9 May 2016. http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/2043(2012)&referer=http://www.un.org/en/sc/documents/resolutions/2012.shtml&Lang=E

[17]Council of Foreign Relations. “Annan’s Peace Plan for Syria.” March 2012. Accessed 20 March 2016. http://www.cfr.org/syria/annans-peace-plan-syria/p28380; Euronews. “Damascus accepts Annan peace plan for Syria.” 27 March 2012. Accessed 20 March 2016. http://www.euronews.com/2012/03/27/damascus-accepts-annan-peace-plan-for-syria/

[18]The Telegraph. “Syrian ceasefire has ‘failed’, says UN chief.” 19 April 2012. Accessed 20 March 2016. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/syria/9213122/Syrian-ceasefire-has-failed-says-UN-chief.html

[19]Geneva Communiqué. See: http://www.un.org/News/dh/infocus/Syria/FinalCommuniqueActionGroupforSyria.pdf

[20]Quinn, Andrew. “Clinton says Syria deal means Assad must go.” Reuters. 30 June 2012. Accessed 20 March 2016. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-crisis-clinton-idUSBRE85T0I720120630

[21]Russia Today. “Annan: Russia, West agree on transition government for Syria.” 30 June 2012. Accessed 20 March 2016. https://www.rt.com/news/syria-summit-geneva-annan-115/

[22]Solomon, Erika. “Syrian rebels say Aleppo theirs ‘within days.’” Reuters. 31 July 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/07/31/us-syria-crisis-rebels-idUSBRE86U0QZ20120731

[23] BBC Arabic. “Rebels withdraw from Salah al-Din and the regime vows the next battle in al-Sukkari.” 10 August 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.bbc.co.uk/arabic/middleeast/2012/08/120809_syria_aleppo_under_fire.shtml?print=1

[24]BBC Arabic. “Clashes continue in Damascus and its countryside.” 13 August 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.bbc.co.uk/arabic/middleeast/2012/08/120813_syria_latest.shtml

[25]Ferris, Elizabeth et al. “Syrian Crisis: Massive Displacement, Dire Needs and a Shortage of Solutions.” Brookings Institute. 18 September 2013. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/reports/2013/09/18-syria-ferris-shaikh-kirisci/syrian-crisismassive-displacement-dire-needs-and-shortage-of-solutions-september-18-2013.pdf p. 6.

[26]OCHA. Humanitarian Bulletin. 12 October 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/system/files/documents/files/ocha-syria-humanitarian-bulletin-issue-10-20121012-en.pdf p.6.

[27]See: Syria Center for Statistics and Research. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://csr-sy.org/?id=475&sons=redirect&l=2&

[28]Hayworth, Michael. “The battle for Aleppo and the failure of the international community.” Amnesty International. 23 August 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.amnesty.org.au/crisis/comments/29577/

[29]O’Bagy, Elizabeth. “The Free Syrian Army.” Institute for the Study of War. March 2013. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/The-Free-Syrian-Army-24MAR.pdf pp. 11-14.

[30]Wilgenburg, Wladimir van. “Assessing the Threat to Turkey from Syrian-Based Kurdish Militants.” Terrorism Monitor. 10 August 2012. Vol. 10. Issue.16. p.6; Arnold, David. “Syria Witness: Aleppo Braces for Onslaught from Assad’s 4th Brigade.” Middle East Voices. 27 July 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://middleeastvoices.voanews.com/2012/07/syria-witness-aleppo-braces-for-onslaught-from-assads-4th-brigade-69086/ ; Ekurd Daily. “Syrian Kurdish forces kill six Assad’s soldiers in Aleppo.” 28 July 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.ekurd.net/mismas/articles/misc2012/7/syriakurd562.htm

[31]Solomon, Erika. “Syrian rebels fight unwanted battle with Kurds.” Reuters. 1 November 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/11/01/us-syria-crisis-aleppo-idUSBRE8A00PY20121101

[32]Wilgenburg, Wladimir van. “Syrian Rebels and Kurdish Group Sign Truce.” AINA. 6 November 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.aina.org/news/20121105192853.htm

[33]Aljazeera English. “Brahimi: Syria government agrees to Eid truce.” 24 October 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2012/10/20121024895639897.html

[34]The Irish Times. “Fire sweeps through Aleppo souk.” 30 September 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.irishtimes.com/news/fire-sweeps-through-aleppo-souk-1.739646; Lubin, Gus. “See What a Famed Syrian Market Looked Like Before It Was Destroyed By Fire.” Business Insider. 29 September 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.businessinsider.com/photos-the-aleppo-souk-2012-9

[35]Holmes, Oliver. “Fighting spreads in Aleppo Old City, Syrian Gem.” Reuters. 1 October 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/10/01/us-syria-crisis-idUSBRE88J0X720121001

[36]See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RIQDOz5Zc_A; See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hgj-dWNff24; See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J_TFB-e_clY

[37]Ali, Mourad. “The economic siege suffocates the safe districts in Aleppo.” Al-Bayan. 18 September 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.albayan.ae/one-world/arabs/2012-09-18-1.1729280

[38]Syria-News. “Activists report water cuts in Aleppo. The Major denies.” Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.syria-news.com/bnews/node/968

[39]France24. “Water cuts in Aleppo and European consensus to sanction the Assad Regime.” 9 September 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.france24.com/ar/20120908-%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A7-%D8%AD%D9%84%D8%A8-%D9%85%D9%8A%D8%A7%D9%87-%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%82%D8%B7%D8%A7%D8%B9-%D9%82%D8%B5%D9%81-%D8%A3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%A8%D8%A7-%D8%B9%D9%82%D9%88%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%A8%D8%B4%D8%A7%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%B3%D8%AF

[40]O’Bagy, Elizabeth. “Syria’s Political Opposition.” Institute for the Study of War. April 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/Syrias_Political_Opposition.pdf pp.9-10.

[41]Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “The Syrian National Council.” Accessed 3 March 2016. http://carnegieendowment.org/syriaincrisis/?fa=48334

[42]Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “The Syrian National Council.” Accessed 3 March 2016. http://carnegieendowment.org/syriaincrisis/?fa=48334

[43]Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “National Coordination Body for Democratic Change.” 15 January 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://carnegie-mec.org/publications/?fa=48369; O’Bagy, Elizabeth. “Syria’s Political Opposition.” Institute for the Study of War. April 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/Syrias_Political_Opposition.pdf pp. 19-20.

[44]France24. “Rebels could resort to chemical weapons, Syria warns.” 8 December 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.france24.com/en/20121208-syria-warns-rebels-may-resort-chemical-weapons-assad-united-nations-islamists

[45]Bar, Herve. “Syrian army Base 46 keeps rebels at bay.” The Daily Star. 9 October 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Middle-East/2012/Oct-09/190657-syrian-army-base-46-keeps-rebels-at-bay.ashx#axzz2CufwPDdP ; See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EYS4QHbRYz8

[46]Bar, Herve. “Syrian army Base 46 keeps rebels at bay.” The Daily Star. 9 October 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Middle-East/2012/Oct-09/190657-syrian-army-base-46-keeps-rebels-at-bay.ashx#axzz2CufwPDdP

[47]Bar, Herve. “Syrian army Base 46 keeps rebels at bay.” The Daily Star. 9 October 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Middle-East/2012/Oct-09/190657-syrian-army-base-46-keeps-rebels-at-bay.ashx#axzz2CufwPDdP; Associated Press. “With capture of regime base, Syrian rebels net a weapons trove.” 22 November 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/refdaily?pass=52fc6fbd5&id=50af25b05

[48]Naharnet. “Syria Rebels Ready Final Assault on Sheikh Suleyman Base.” 24 November 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.naharnet.com/stories/ar/62099 ; Al-Wasat. “Syrian Forces repels rebel attack on a military base in Aleppo countryside.” 6 July 2014. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.alwasatnews.com/3728/news/read/717701/1.html; AFP. “Syrian army repels rebel attack on base: watchdog.” 21 November 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/syrian-army-repels-rebel-attack-on-base-watchdog.aspx?pageID=238&nid=35151&NewsCatID=352

[49]Al-Riyadh. “An Uzbek led the final assault on Sheikh Suleyman base in Aleppo.” 11 December 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016.http://www.alriyadh.com/791701; Roggio, Bill. “Al Nusrah Front, foreign jihadists seize key Syrian base in Aleppo.” The Long War Journal. 10 December 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2012/12/al_nusrah_front_alli.php

[50]Surk, Barbara. “Islamist fighters take army base as rebel forces make gains in Aleppo.” The Independent. 16 December 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/islamist-fighters-take-army-base-as-rebel-forces-make-gains-in-aleppo-8421110.html; Alahram Online. “Free Syrian Army top commander killed in Syria’s Aleppo.” 15 December 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/2/8/60568/World/Region/Free-Syrian-Army-top-commander-killed-in-Syrias-Al.aspx

[51]O’Bagy, Elizabeth. “The Free Syrian Army.” Institute for the Study of War. March 2013. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/The-Free-Syrian-Army-24MAR.pdf pp. 16-27

[52]Bolling, Jeffry. “Rebel Groups in Northern Aleppo Province.” Institute for the Study of War. 29 August 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/Backgrounder_RebelGroupsNorthernAleppo.pdf p.8.

[53]O’Bagy, Elizabeth. “The Free Syrian Army.” Institute for the Study of War. March 2013. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/The-Free-Syrian-Army-24MAR.pdf p.29.

[54]Al-Akhbar. “Al-Nusra Front fighters declare ‘No Fly Zone’ over Aleppo: Video.” 22 December 2012. Accessed 3 March 2016. http://english.al-akhbar.com/node/14466

The Aleppo Project

The Aleppo Project